Steppenwolf was a Canadian-American rock band, prominent from 1968 to 1972. The group was formed in late 1967 in Los Angeles by lead singer John Kay, keyboardist Goldy McJohn, and drummer Jerry Edmonton (all formerly in Canadian band The Sparrows). Steppenwolf sold over 25 million records worldwide, released eight gold albums and 12 Billboard Hot 100 singles, of which six were top 40 hits, including three top 10 successes: "Born to Be Wild", "Magic Carpet Ride", and "Rock Me".

Jack London and The Sparrows began as a beat group and played heavily on Dave Marden's English background. Their early repertoire reflected the influence of the “British invasion” and London even went as far as coaxing the others to “fake” English accents, in order to convince the audience that they had just arrived from England. During September 1965, The Sparrows added singer/songwriter and guitarist John Kay to the line-up.

Throughout the first few months of 1966, the group consolidated its following on the local club scene. Realizing that they needed to attract a wider audience, Sparrow (as the band was now called) attracted the interest of electronics executive Stanton J. Freeman, who became their manager and arranged for a booking at Arthur, Sybil Burton's hot new club in New York. Freeman then flew them to New York so the A&R people at the major record companies could see them perform. Sparrow were so well received that over the next five months, they commuted back and forth between Toronto and New York. While in the Big Apple, Sparrow also appeared at the Barge in Westhampton on Long Island and at another New York club, the Downtown.

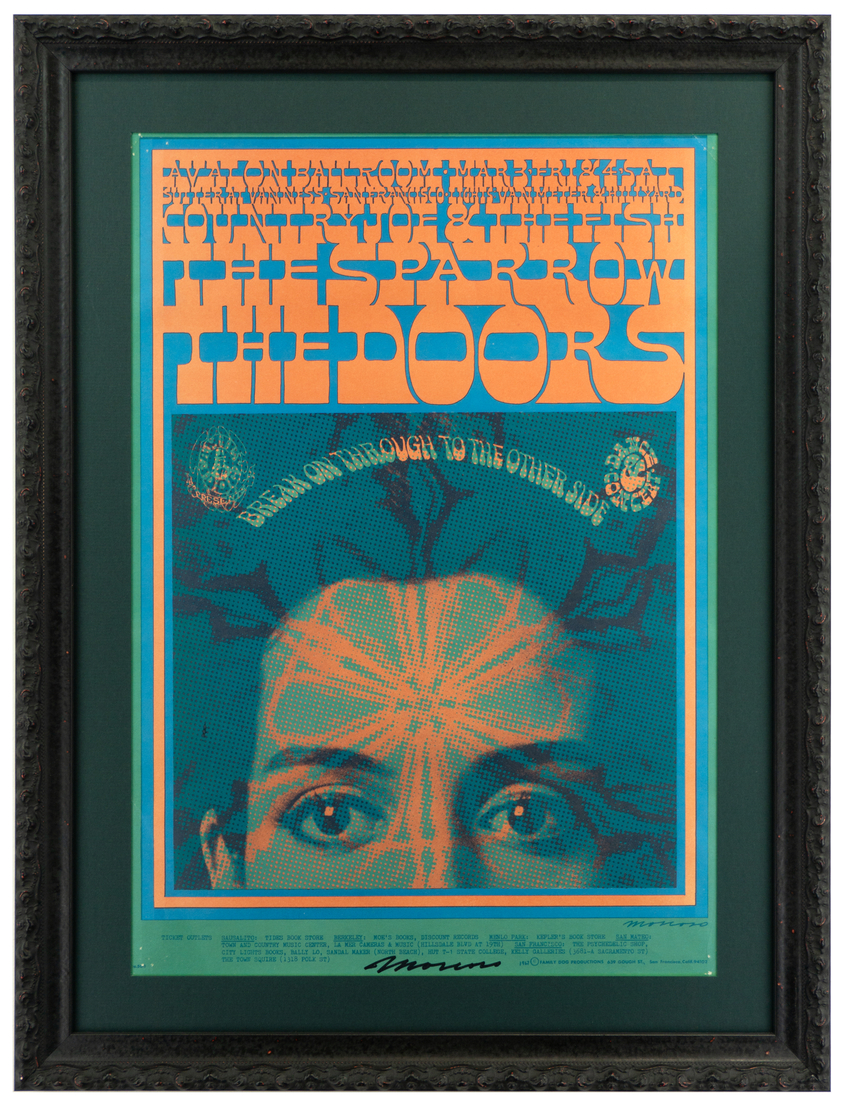

By then, the band had abandoned Canada (and New York) for the warmer climes of California. During November 1966, Sparrow debuted at It's Boss in West Hollywood. Shortly thereafter, they moved to San Francisco where they performed at the Ark in nearby Sausalito as well as the Matrix and the Avalon Ballroom. Sparrow continued to commute back and forth between Los Angeles and San Francisco throughout the first six months of 1967, performing alongside The Doors, The Steve Miller Band and many others. During June, Dennis Edmonton announced his decision to go solo and the band recruited American guitarist Michael Monarch in early July. Edmonton subsequently changed his name to Mars Bonfire.

In late 1967, Gabriel Mekler urged Kay to re-form Sparrow with a name change to Steppenwolf, inspired by Hermann Hesse's novel of the same name. Steppenwolf's first two singles were "A Girl I Knew" and "Sookie Sookie". The band finally rocketed to worldwide fame after their third single, "Born to Be Wild", was released in 1968, as well as their version of Hoyt Axton's "The Pusher". Both of these tunes were used prominently in the 1969 counterculture cult film Easy Rider. In the movie, "The Pusher" accompanies a drug deal, and Peter Fonda stuffing dollar bills into his Stars and Stripes-clad fuel tank, after which "Born to Be Wild" is heard in the opening credits, with Fonda and Dennis Hopper riding their Harley choppers through the America of the late 1960s. The song, which has been closely associated with motorcycles ever since, introduced to rock lyrics the signature term "heavy metal" (though not about a kind of music, but about a motorcycle: "I like smoke and lightning, heavy metal thunder, racin' with the wind...").

In 1969 Steppenwolf released their most radical album, Monster. Angry and politically charged, it opens with the deceptively airy Monster-Suicide-America, a rambling, psyche-pop mind-bomb that expressed with nimble dexterity the daily anguish of life in the US during the Vietnam war. Songs like Draft Resister and Fag burned with a righteous anger a million miles away from the party- stomping bacchanalia of Magic Carpet Ride. The days of easy riding were definitely over. ‘It’s time to get our heads together,’ Kay sang on the bluesy rabble-rouser Power Play. ‘Let ’em know we’re awake.’

“When we turned in the Monster album to our record company, they asked us where the hit single was,” Kay remembers. “We said: ‘It’s not about a hit, you numbskulls. It’s a political concept album.’ So they looked at us and said: ‘Well, okay, what do we do with it?’ I said: ‘Man, you take it college campuses.’ So they did that.”

The album yielded two Top 40 hits, including the 10-minute title song and the super-grooving Move Over. More importantly, it also struck a chord with the distraught and disenfranchised in those turbulent times. As Kay explains, Monster’s rebel yell still echoes even today.

“Sometimes you throw a pebble in the pond, but the ripple effect doesn’t reach you for many years later”, he says. “About a week ago somebody turned me on to the Rolling Stone website, where one of their writers was readdressing the Monster album, writing about how relevant it is now. At the same time, I get a call from the London Observer from a guy who’s a war correspondent there. He was at our Royal Albert Hall show in the early 70s, and he’s been a Wolf fan ever since. He told me the Monster album is what got him on his way. On the same day, I got a letter from this lawyer in the deep south. He tells me that the Monster album is what got him started, and he’s been a lawyer for 25 years, representing the common man to fight against the bullies of the world. The gold records are fine, but there’s a whole shoebox full of letters like that. And they mean more than any trophy.

Despite the lingering influence of Monster, the album was not the smash that previous records were, and the band’s slow decline from the charts began. As Kay explains, the punishing recording and touring schedule the band had taken on four years previously was finally taking its toll.

“Once we caught our first wave of success, it was an intense, blurred period. Because we were so young and so unsophisticated, with respect to the recording industry, we signed a recording deal that really came out of the 1940s or 50s. When we signed the initial deal, we didn’t have a pot to piss in. Some of our gear was in the hock shop, and there was no money for a lawyer and we didn’t have any management yet. There were only two things that we insisted on. One was that we no longer had to release singles. We figured the time for singles was over. We wanted a guarantee that we could make an album, and that the label would release it. The other thing was that we needed $1,500 to get our amplifiers out of hock. So they said: “Okay, you can have that,” and that was it.

“So basically, the contract said: ‘You’re going to deliver two albums a year.’ That was based on some crooner being called into the studio twice a year. He’s got an A&R man, he’s picked the songs, he’s learned the tunes, he’s got the orchestra rehearsed, and three days later he’s got an album. Well, these were the days when people were writing their own songs. We had to go out on the road to promote the album that was just released, then we had to go to Europe, come back to the US to do television, all this stuff. Two records a year was just an absurdity. Somewhere down the line, bands like The Eagles said: ‘I don’t care what the contract says, you’re gonna get the album when it’s ready.’ But that was years later. For us, well, we signed this contract, and the label is pushing us, so we’d better get these two records out.

“It hurt us. We ran out of juice after a while. We should have waited. To some extant that was really the reason why 1971 I said: ‘Listen, guys. I want to put a stop to this. And I don’t want to be responsible for everyone’s livelihood. So if we want to retire the name and go our separate ways, I’m okay with that.’ I was basically burned out. With hindsight, that could have been done much better; we could have had more enlightened management that would have stood up to the label, a lot of things. But I’m not complaining. There are worse things than what happened to us by a long shot. And nobody ran off to Ecuador with our money.”